(I wrote and performed the following story for VAMP, a showcase put on by So Say We All, a San Diego based non-profit arts organization. The performance was held at Whistle Stop Bar, which plays a crucial role in the story, one that I had every intent to tell here first, but for whatever reason never got around to doing so. Until now. I’ve tried my best to simulate the performance by including some of the many pictures that were projected behind me during the reading.)

I don’t know why I thought that walking 130 miles from LA to San Diego would be a good idea, but two years ago now I was convinced by summer’s end it would be done. I’d just wrapped up a stint as a full-time English Lit grad student at San Diego State, and was determined to become a full-time walker. I blame this lack of foresight on my discovery of an avant-garde movement called psychogeography. Coined in 1950s Paris, popularized decades later in London, and spread around the globe, psychogeography calls for a pedestrian exploration of urban landscapes, seeped in a long literary tradition. Under its influence, I started to see how walking could be experimental, self-empowering, and a whole lot of fun.

So, here I am, dumped out of the cloistered world of academia, and taking to the streets of San Diego to start a psychogeographic movement of one, complete with a blog. The further I stretch my limits, the further I set my sights, so why not L.A.? They say nobody walks in L.A., but the idea of walking home from there – while arbitrary and totally absurd – sounds strangely appealing. We all love to complain about the commute, but a relaxing 130-mile stroll could be a source of inspiration, and give me a sense of purpose at a time when I could use one. I set the date for August 2nd, plan a route requiring the fewest steps, finding places to stay along the way, so that after five long days I would end right here at the Whistle Stop, a mere block away from where I’d be moving in with my girlfriend the following week.

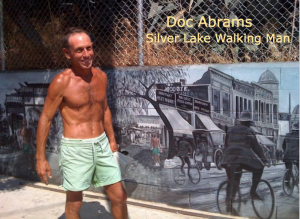

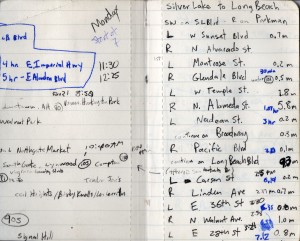

The trip starts at 7am in Silver Lake. I set out after a quick stretch on Sunset in front of a mural turned memorial for local legend, Doc Abrams, The Silver Lake Walking Man. I figure I can walk in honor of Doc, who, until his recent passing, could be seen reading the paper along his daily loop through the area. Who knows? Maybe someday I could be known as the South Park Walking Man. I wind my way through Monday morning, relying on directions scribbled out in a mini-moleskine, which would lead me through South Central before ending at a friend’s house in Long Beach.

Downtown streets are a breeze compared to the six-mile gauntlet through the entirely industrial city of Vernon. With towering warehouses, big rig back drifts, and a cement spinal cord of underground railroad tracks splitting up the center, this lifeless zone has me feeling stuck in some lost circle of Dante’s Inferno.

I escape through the more residential cities of Walnut Park, South Gate, and Lynwood. All signs turn to Spanish, and people are spotted using sidewalks, paying no attention to the only white guy around for miles.

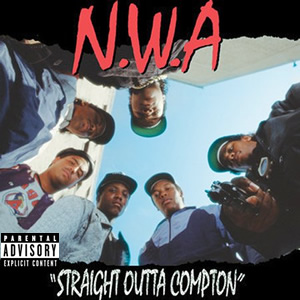

Once in Compton it becomes painfully clear this is nothing like those walking tours they have for homes of Hollywood stars. I’m not on a pilgrimage to see where “Fuck tha Police” was penned. I figure I can walk hard, walk fast, and fend off any potential troublemakers with my super-macho Mickey Mouse hat.

But not long after crossing into city limits, I’m stopped by a man in a rusty red pickup asking in a familiar Spanish for directions to “Atlantic”. I explain that I have no clue where “Atlantic” might be, that I’m merely passing through, and am sorry to be of no help. Convinced I’m lost, he does the unexpected: he offers me a ride. I decline, and he drives off more puzzled than when he pulled up. I don’t know if I should see this man’s decision to ask me for directions as flattery or foolishness, but something about our interaction makes me feel like Compton has accepted me. No matter how much of an outsider I am, by walking in an urban environment where it’s seen as normal, there comes a feeling of intimacy with its inhabitants. Later that afternoon, soaking my blistered feet in my host’s jacuzzi, I look to days ahead, not realizing how lonely they might be.

Day two has me reaching the coast, crossing the Orange County line, and cruising down to Huntington Beach, Surf City USA, where the US Open of Surfing is in full swing. I should feel comfortable here, having come to these in years past. And though the days of frosted tips and puka shells are long behind me, I don’t expect to be seen as such an eyesore as I hobble along the boardwalk south of the pier where suntanned teens chuckle and point at the only person in sight wearing closed-toed shoes. Or is it the hat?

I’m lured into a Starbucks in Newport Beach by the promise of air conditioning, a clean restroom, and a decentish cup of coffee. I overhear two cops bragging to a barista about how busy they’ve been lately, prompting her to say, “Yeah, it’s like we’re in Compton, or something.” While they all have a good chuckle, I resist the urge to speak up in defense of the city that a day earlier let me pass through without sounding a siren.

I’m lured into a Starbucks in Newport Beach by the promise of air conditioning, a clean restroom, and a decentish cup of coffee. I overhear two cops bragging to a barista about how busy they’ve been lately, prompting her to say, “Yeah, it’s like we’re in Compton, or something.” While they all have a good chuckle, I resist the urge to speak up in defense of the city that a day earlier let me pass through without sounding a siren.

I spend the rest of the afternoon cutting through coves before checking in at the cheapest motel for miles. I have difficulty convincing the elderly Asian manager that I have walked there. She insists I fill in the line asking for make and model of my vehicle, and doesn’t seem to appreciate it when I write, “White Nikes, size 10”. Numerous online reviews complain of drug dealers and sexual predators living here as permanent residents. While I have no recollection of being drugged or raped that night, I appreciate their help in keeping the cost low.

I spend the rest of the afternoon cutting through coves before checking in at the cheapest motel for miles. I have difficulty convincing the elderly Asian manager that I have walked there. She insists I fill in the line asking for make and model of my vehicle, and doesn’t seem to appreciate it when I write, “White Nikes, size 10”. Numerous online reviews complain of drug dealers and sexual predators living here as permanent residents. While I have no recollection of being drugged or raped that night, I appreciate their help in keeping the cost low.

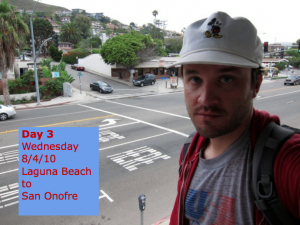

I’m trudging through Laguna Beach Wednesday morning, where my morale receives a blow as a teenager passes me up on foot, without even a nod, before disappearing around the corner. Loneliness kicks in; for the rest of the day no eye contact with anyone.

By the time I get to San Juan Capistrano I’m ready to fly as far south as possible. I stop at a storefront in San Clemente with a sign promising foot massages. As tempting as it is to step inside, I figure they’d turn me away at first sight of my festering blisters.

Disappointment kicks in as I reach San Onofre, realizing that the campsite I’d booked is a few miles south of what I’d mapped out. Somewhere down the long stretch of numbered campsites my girlfriend pulls up; demands I get in her car.

“And defeat the whole purpose?! Never! Keep driving!”

I finally come to where she and a few friends sit roasting hot dogs. Most of the night is spent in a tent re-bandaging blisters. I seriously contemplate calling it quits. But I awake the next day determined to press on.

At Camp Pendleton, I’m greeted by the lone sentry: “Can I help you?” After asking if I could pass through to Oceanside, he becomes the first person in four days to ask me why. I hoped he’d be a little more suspicious, use harsher interrogation techniques, maybe even strip search me. Finally, my moment to enlighten and entertain someone with my harrowing tales of the open road, and all I’m able to get out is: “Because I can.” Puzzled, he points down the road: “Just stay to the right.”

For the next ten sidewalk-free miles, I think about what I had said to the sentry. What did I mean by “because I can”? What am I trying to prove? There is no story to find. My thoughts consist of pain and the next resting place. But, if this is going to be a self-imposed rite of passage, I won’t let anything stop me from seeing it through. I make it off the base, and reach my friend’s house in Carlsbad with enough time to recover in preparation for the incredibly long thirty-five-mile last day.

Friday morning I find my stride, largely thanks to distractions that keep my mind occupied. I pick up newspapers and realize that the late Doc Abrams was onto something: that reading is a good remedy for pain.

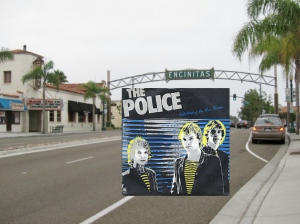

I listen to an iPod mix I made for the trip. I would walk “500 Miles” with The Proclaimers through La Costa, singing “I’m gonna be the man who comes back home to you.” Leucadia witnesses me “Walk This Way” Run-DMC style, while poor Encinitas hears me “Walking On The Moon” with The Police. Stopping under the Cardiff Kook, Edwin Starr chimes in to remind me that I was “Twenty Five Miles” from home, and while “my feet are hurting mighty bad,” I now have a go-to song to help me through the rest of the day.

Cresting the two mile vertical climb at Torrey Pines, an intense pain in my right achilles reduces me to a pathetic hobble, giving me serious doubts that I could go much further without causing immeasurable damage to my uninsured body. “Come on feet, don’t fail me now,” Starr pleads for me, “I’ve got – 10 more miles to go.” My painkillers kick in as I descend into Mission Valley, where I finally feel that home is just over the hill and around the bend.

I push up Texas with visions of a welcoming party reaching the hundreds. I challenge friends to meet me somewhere along my final stretch through North Park, forgetting that most people can’t imagine walking two whole miles. My sister is the only person to pull through. Together, we press down 30th, over Switzer Canyon into South Park. Home at last!

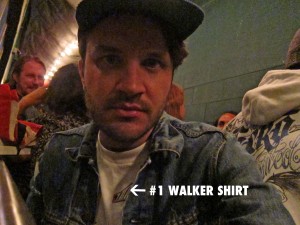

That whole walk across the street at Juniper went by faster than the slow-motion finish I’d been fantasizing about. There was a small welcoming party, complete with a red-ribbon finish line, American-flag banners, and balloons. A friend made me a T-shirt reading “#1 Walker” that I still wear with pride.

But not much else came of it.

There’s no San Diego Psychogeographic Society, and I don’t expect to be depicted on murals anytime soon. The blog never really took off. Yet, I’m still walking as much as possible. I’ve even picked up some work teaching writing classes at City College, a mere two mile stroll away. I give accurate directions to lost drivers, get my coffee from anywhere but that one place, and every once in awhile I’m able to convince people to join me.